The human joint pain hip represents a marvel of evolutionary engineering, a primary weight-bearing ball-and-socket synovial joint that facilitates a vast range of motion while maintaining the structural integrity required for bipedal locomotion. However, the complexity of this anatomical region also makes it susceptible to a diverse array of pathologies, ranging from acute soft-tissue inflammation to chronic degenerative conditions.

When individuals experience hip joint discomfort, the impact is rarely localized; it ripples through the kinetic chain, often manifesting as hip pain back issues or compensatory strain in the knees and ankles. Understanding how to relieve joint pain in the hip requires a nuanced appreciation of the underlying biological mechanisms, the specific diagnostic markers that differentiate various conditions, and the comparative efficacy of modern therapeutic interventions.

Anatomical Foundations and the Biomechanics of Hip Pathogenesis

The hip joint is formed by the articulation of the acetabulum of the pelvis and the femoral head. This interface is covered by articular cartilage—a smooth, friction-reducing tissue that allows for fluid movement. Surrounding the socket is the acetabular labrum, a fibrocartilaginous ring that provides depth to the socket and assists in joint stability through a negative pressure “seal” mechanism. When this seal is compromised, such as in a hip labral tear, the mechanical efficiency of the joint diminishes, leading to the early onset of osteoarthritis in the hip.

The stability of the hip is further bolstered by a robust capsule and several key ligaments, including the iliofemoral, pubofemoral, and ischiofemoral ligaments. Beyond these passive structures, the dynamic stability of the joint depends on the surrounding musculature. The gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus, along with the iliopsoas, adductors, and deep rotators, must function in perfect synchrony to manage the immense forces generated during movement.

Clinical research indicates that during a standard gait cycle, the hip joint is subjected to compressive forces equivalent to three to five times an individual’s total body weight. This mechanical load is exacerbated by architectural abnormalities, such as femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), where bone-on-bone contact occurs prematurely during range-of-motion activities, often leading to chronic hip pain in younger, active populations.

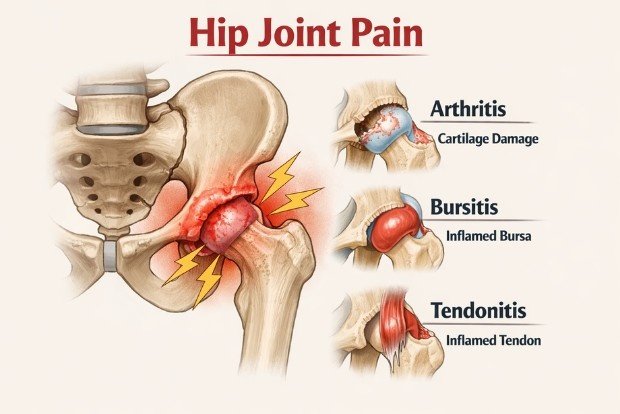

The Etiological Spectrum: Differentiating Hip Pain Causes

A systematic approach to hip pain relief begins with an accurate diagnosis. The location of the symptoms serves as a primary diagnostic filter. Pain localized to the groin or the anterior aspect of the hip typically suggests an intra-articular pathology—something occurring within the joint itself. Conversely, pain on the lateral aspect, often described as hip joint discomfort on the outer thigh, is frequently associated with extra-articular structures like the bursae or tendons.

Intra-Articular Pathologies: The Arthritis Landscape

Osteoarthritis (OA) remains the most prevalent cause of chronic hip pain, characterized by the progressive “wear-and-tear” of the articular cartilage. As the cartilage thins, the joint space narrows, and the body attempts to stabilize the joint by producing osteophytes. This degenerative cascade leads to joint stiffness in the hip, particularly after periods of inactivity or upon waking in the morning. While OA is primarily a mechanical failure, it involves secondary inflammatory processes that contribute to the sensation of deep, aching pain.

In contrast, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) represents a systemic, autoimmune assault on the synovial membrane. Unlike the isolated nature of OA, RA often affects multiple joints simultaneously, and patients may report concurrent joint pain left hand symptoms or involvement of the feet. The inflammatory process in RA is more aggressive, leading to rapid joint destruction if not managed with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

| Feature | Osteoarthritis (OA) | Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) |

| Primary Mechanism | Mechanical wear and cartilage loss | Autoimmune inflammation of synovium |

| Symmetry | Often unilateral or asymmetric | Typically symmetrical involvement |

| Morning Stiffness | Usually lasts <30 minutes | Often lasts >30-60 minutes |

| Systemic Symptoms | Generally absent | Fatigue, fever, loss of appetite |

| Commonly Affected | Weight-bearing joints (hips, knees) | Small joints (hands, feet) first |

Extra-Articular Conditions: Bursitis and Tendinopathy

Hip bursitis, specifically trochanteric bursitis, involves the inflammation of the fluid-filled sacs that cushion the friction between bone and soft tissue. Patients with this condition typically experience sharp, localized pain on the bony prominence of the outer hip. This pain is often exacerbated by lying on the affected side, climbing stairs, or standing for prolonged periods. While bursitis can be debilitating, it rarely limits the actual range of motion of the joint in the same way that arthritis does; rather, the pain itself acts as the primary limiting factor for activity.

Acute Crisis Management: Recognizing Red Flags

In the pursuit of fast relief, clinicians must first screen for “red flag” symptoms that necessitate immediate medical or surgical intervention. Septic arthritis, a joint infection, is a critical diagnosis that presents as sudden, intense joint pain with fever. The affected joint is often hot, swollen, and exquisitely tender to any movement. If not treated within 24 to 48 hours with surgical drainage and intravenous antibiotics, the bacterial enzymes can permanently destroy the articular cartilage.

Similarly, a hip fracture, particularly in elderly populations with osteoporosis, is a medical emergency. Typical presentation includes severe pain after a fall, an inability to bear weight, and a leg that may appear shortened or externally rotated. Identifying these conditions early is the most critical step in treatment for hip pain, as the window for successful intervention is narrow.

Pharmacological Strategies for Symptom Suppression

The pharmacological management of hip pain is governed by the need to balance analgesic efficacy with the patient’s systemic health profile. The joint pain best medicine for an individual depends heavily on the underlying inflammatory state.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs are the cornerstone of hip pain management for both acute flare-ups and chronic osteoarthritis. These medications work by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, which are responsible for the synthesis of prostaglandins—lipids that promote pain, fever, and inflammation.

Data from the Oxford League Table of Analgesic Efficacy provides a quantitative look at how different NSAIDs perform. The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) is a clinical metric used to express the effectiveness of a treatment; a lower NNT indicates a more effective medication.

| Medication and Dosage | NNT for 50% Pain Relief | Lower CI | Upper CI |

| Ibuprofen 800 mg | 1.6 | 1.3 | 2.2 |

| Diclofenac 100 mg | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.2 |

| Naproxen 440 mg | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.9 |

| Aspirin 1200 mg | 2.4 | 1.9 | 3.2 |

| Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) 1000 mg | 3.8 (estimate) | 2.2 | 4.0 |

The Role of Acetaminophen and Topicals

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is frequently utilized for patients who cannot tolerate NSAIDs. Although it is effective for pain and fever, it has negligible anti-inflammatory effects, making it less ideal for inflammatory hip joint inflammation. Recent clinical guidelines from the ACR and Arthritis Foundation have actually downgraded the recommendation for acetaminophen in hip OA, suggesting it provides only modest benefit compared to placebo in high-quality trials.

Topical agents, such as diclofenac gel (Voltaren), offer a localized alternative with fewer systemic side effects. However, their efficacy in the hip is often limited by the depth of the joint. Unlike the knee or hand, where the joint is relatively superficial, the hip joint is encased in thick layers of muscle and fat, which may prevent topical medications from reaching the intra-articular space in therapeutic concentrations.

Biomechanical Weight Management: The Physics of Relief

One of the most profound strategies for hip pain management is weight reduction. Because the hip acts as a fulcrum for the body’s weight, the mechanical advantage (or disadvantage) is significant. The force on the hip joint can be simplified through the following biomechanical relationship:

$$F_{hip} = k times BW$$

Where $F_{hip}$ is the force on the joint, $BW$ is body weight, and $k$ is a constant that varies based on activity (typically between 3 and 5 for walking).

Clinical data demonstrates that losing just 10 pounds can reduce the cumulative load on the hip joint by 30 to 50 pounds with every step. For individuals with advanced arthritis, this reduction in pressure can be the difference between needing an immediate hip replacement surgery and being able to manage symptoms through conservative means.

Pregnancy and the Hip: Managing Hormonal Laxity

Hip pain during pregnancy is a distinct clinical entity, often referred to as pelvic girdle pain (PGP). This condition typically occurs due to the release of the hormone relaxin, which softens the ligaments and connective tissues in the pelvis to prepare for childbirth. While this laxity is functionally necessary, it results in joint instability and increased strain on the muscles surrounding the hip.

In addition to hormonal changes, the shift in the center of gravity as the uterus grows forces the lumbar spine into an increased lordosis, leading to hip pain back referral. Relief strategies during pregnancy focus on:

- Supportive Posture: Standing tall and avoiding the “leaning back” posture that compensates for the weight of the baby.

- Pelvic Stability: Using a maternity belt to provide external support to the sacroiliac and hip joints.

- Sleep Alignment: Sleeping on the side with a pregnancy pillow between the knees to prevent the top leg from pulling the pelvis out of alignment.

- Manual Therapy: Osteopathic or chiropractic care focused on gentle mobilization to address mechanical imbalances.

Physical Therapy and the 2025 Clinical Practice Guidelines

The 2025 Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) from APTA Orthopedics has established clear “Grade A” recommendations for the management of hip OA, focusing heavily on active rehabilitation over passive modalities.

Therapeutic Exercise Protocols

Exercise is the primary non-surgical intervention for maintaining hip joint function. A well-rounded program must address three pillars: strengthening, flexibility, and aerobic capacity.

- Strengthening (Posterior Chain Focus): Weakness in the gluteus medius and maximus leads to a “Trendelenburg gait,” where the pelvis drops on the opposite side during walking, further irritating the hip joint. Exercises such as glute bridges, clamshells, and side-lying leg raises are essential for stabilizing the pelvis.

- Flexibility (Range-of-Motion): Stretching the hip flexors (iliopsoas) and the piriformis can alleviate “snapping” sensations and reduce the compressive force on the joint.

- Hydrotherapy: For those with severe pain, aquatic therapy provides a unique environment where the buoyancy of the water offloads the joint while the viscosity provides resistance for strengthening.

The Evolution of Manual Therapy and Dry Needling

The 2025 guidelines have significantly elevated the role of dry needling for hip pain relief. This technique involves inserting fine needles into myofascial trigger points in the gluteal and iliopsoas muscles. High-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that dry needling provides short-term (3 weeks) improvements in pain, muscle extensibility, and function in patients with Grade II and III hip OA.

Manual therapy also remains a strong recommendation, particularly joint mobilization techniques such as “long-axis distraction.” In this procedure, the clinician applies a gentle traction force to the leg, which creates space within the joint capsule, temporarily reducing the pressure on the sensitized synovial lining and encouraging the flow of synovial fluid.

Nutritional and Integrative Approaches to Inflammation

Systemic inflammation is a significant modulator of joint pain. Chronic hip pain management is increasingly incorporating nutritional interventions to decrease the “inflammatory load” on the body.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Supplements such as fish oil inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-$alpha$) and interleukin-6 (IL-6).

- Curcumin (Turmeric): Curcumin is a potent antioxidant that interferes with the NF-$kappa$B pathway, a key regulator of the inflammatory response. For maximum absorption, curcumin should be taken with piperine (black pepper) and healthy fats.

- The Mediterranean Diet: An umbrella review of 14 meta-analyses suggests that a diet high in fiber, polyphenols, and monounsaturated fats (like olive oil) can significantly reduce disease activity scores in inflammatory arthritis.

- Epsom Salt Soaks: The magnesium sulfate in Epsom salts acts as a natural muscle relaxant. Magnesium is a crucial cofactor for over 300 enzymatic reactions in the body, including those involved in muscle contraction and nerve signaling.

Interventional Medicine: From Injections to the Surgical Frontier

When conservative strategies reach their limit, interventional options offer a bridge to long-term relief.

Intra-Articular Injections

Corticosteroid injections remain the most common interventional treatment for hip arthritis and bursitis. While they provide significant, rapid relief by suppressing inflammation, their effect is temporary, and repeated use can potentially accelerate cartilage loss. Hyaluronic acid injections, often called “gel shots,” aim to restore the lubrication of the joint, though the evidence for their efficacy in the hip is less robust than in the knee.

Surgical Innovations

The landscape of hip surgery has evolved from aggressive open procedures to minimally invasive techniques. Hip arthroscopy allows surgeons to repair labral tears and address bony impingement through small incisions, significantly reducing recovery time. For those with advanced, end-stage degeneration, hip replacement surgery remains the most successful procedure in modern orthopedics. Modern replacements utilize advanced materials like ceramic-on-cross-linked polyethylene, which can last 20 to 30 years or longer, allowing even younger patients to return to high levels of activity.

Dr. Shashikanth Rasakatla is a leading Orthopedic Surgeon, Joint Replacement Specialist, and the founder of the Sri Shashikanth Pain Management and Sports Injuries Centre in Karimnagar. He is passionate about using advanced, minimally invasive techniques to help patients overcome pain and return to an active lifestyle. Through his writing, he aims to provide clear, trustworthy information on joint health and sports medicine.

Leave a Reply